Some spoilers.

Left Neglected is a novel about an intelligent, driven, Type A woman, Sarah Nickerson, who crashes her car and injures her brain due to driver distraction. The novel’s first chapters are descriptions of her days in the week preceding the crash. Each chapter begins with a dream that reflects where Sarah’s mind, which her conscious mind refuses to understand. Life is about wealth, status, work — having material success and putting job first at the expense of relationships like most of North American society. Her core ability resides in her brain and her intelligence. The car crash didn’t take her intelligence away, but it did take away what it had given her.

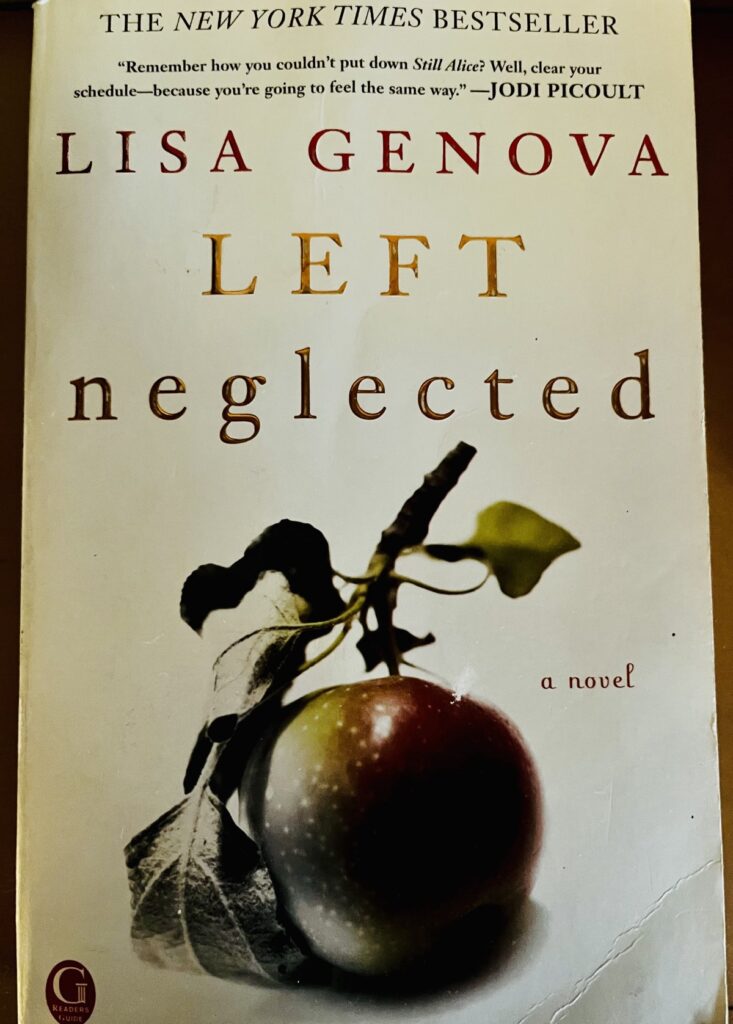

A decade ago, a fellow bible study member loaned me Left Neglected. In the novel, Sarah was the same age I was when the universe thrust me into the unwanted life of brain injury. But unlike her, I didn’t have the fairy tale support and a new, exciting life within a year.

Yet I gained something that Sarah didn’t, for in all her research, Sarah’s author Lisa Genova never heard about neurostimulation and/or neuromodulation to restore broken neurons and neural networks. (You can read my story in Concussion Is Brain Injury: Treating the Neurons and Me.)

I borrowed Left Neglected reluctantly. The lender brushed away my trouble reading, that I didn’t know when I’d get to it, and pushed it into my hands. So much reminded them of me and my travails; whenever I could read it was OK with them.

I moved it around my place every time I had rare energy to dust my bookshelves. It stared back passively, reminding me of what I couldn’t do anymore because in 2000 one driver needed to tailgate down a highway hill and another felt speeding was the only option for her. Although I regained my reading comprehension in 2018 — after I’d fully and finally given up on finding any treatment to restore it — I buried Left Neglected under a pile of books so that it would stop taunting me.

But on the fifth of January in this new year, two weeks after I suddenly decided to take a complete social media, computer, and writing break — a break from the horrible world — I fished it out, ready to read it. And I finished it on January 13th, pretty remarkable speed from where I began after my brain injury and after finishing the Lindamood-Bell visualizing and verbalizing reading comprehension program in 2018 to restore my reading.

I made an effort to visualize and verbalize this book properly, to think consciously about Sarah’s dreams and what they were reflecting about her life and how she really felt about it. The problem for me was that Genova tells rather than shows, giving a kind of flat-emotion to the novel. The emotions for me came from my own experience rather than feeling what Sarah was feeling. For example, Sarah cried. That’s the word Genova used — “cry” — not words like: I blubbered, bawled, sobbed, cried silently, my eyes wettened, tears rolled down and dripped off my chin. And so there’s no differentiation between her five minutes of crying at her desk, hidden from her colleagues, and the crying she did after her injury. I also found her lack of crying a little unrealistic.

Brain injury recovery includes crying from frustration, grief, loneliness, anger, fed-upness, overstimulated, being overwhelmed. Pretty much anything can spout tears in your eyes or hours of sobbing. One person I know with brain injury described himself as having leaky eyes. A perfect description!

Even so, I found the novel enjoyable until Sarah began her rehab. That’s when I started to get mad. Her rehab was so basic, so last century. I had to remind myself that Genova probably wrote this novel in 2010, and it was published in 2011.

The ADD Centre where I received my brain biofeedback treatments to rewire, regrow, and restore my neurons and neural networks hadn’t yet found and researched tDCS (transcranial direct current stimulation). Battery-operated microvolt tDCS stimulates a targetted area of the brain while you’re engaging in the activity you want to restore. PONS is another neurostimulation treatment that works to restore balance in people with motor skill deficits, and it didn’t come on the scene until after 2011 as well. Yet by 2010, the ADD Centre and I had already proven four years previously that brain biofeedback restores concentration in a person with brain injury. In addition, audiovisual entrainment had been used for at least a decade in treating brain injury.

Sarah’s rehab team could’ve provided brain biofeedback treatments so that she could regain her concentration. That would’ve reversed her distractibility and allowed her to better practice her left neglect rehab. They could’ve used audiovisual entrainment prior to each left neglect rehab session to enhance her focus and thinking brainwaves so as to make it easier for her to practice and, as well, increase the effects of her practice.

What really gets me about Genova not having researched these methods is that 13 years after the publication of her novel, rehab probably hasn’t progressed beyond what Genova describes. I’d like to see a story, novel or movie, that uses neurostimulation as the primary treatment for brain injury!

As an aside, she doesn’t describe Sarah’s at-home rehab hardly at all. There’s like a couple of scenes, but no real feel of how much it’s a part of life. Nothing about the outpatient rehab person other than insurance stopped paying for them. What did the therapist do with Sarah at home? What was at-home therapy like compared to inpatient rehab? What’s it like to live without needed rehab after insurance (or in my case the rehabilitation hospital’s owners and government medicare) stop funding it? How does a person feel about having the system give up on you? The answers are a big part of life with brain injury. And Genova does a poor job of conveying the hopelessness and the feeling of being tossed on the trash heap. She tells us Sarah’s reaction to being discharged; she doesn’t immerse the reader in the emotions then or when outpatient rehab ends.

This lack conveys the false idea that one can regain a rewarding, exciting life in only a year and that having no full recovery is a-OK because life with brain injury is good. Give me a fucking break. This novel reflects the problem of every story, real or fictional, about brain injury. People want their brains back. Period. They may accept the limitations standard medical care and insurance (private or government) imposes on them; but we all want our fucking brains back in full! I was able to use my educational background to find treatments, but most can’t. Sarah, for all her intelligence and drive, never questions nor searches for treatments beyond what rehab provides. At best, she talks about being able to do more than what her health care team believes. But what she considers doing more is a poor shadow of what neurostimulation and neuromodulation would’ve given her.

The other false idea is that her marriage remains intact, family sail in to fully support and happily search for ways to improve her quality of life, friends encourage her. Mind you, Sarah doesn’t really have a circle of friends, and so there’s no sense of her social network shrinking to nothing like happens with most people with brain injury. Loneliness and struggling alone are real. In the real world, when Sarah fell down trying to retrieve coffee beans from the refrigerator there would’ve been no one to wait for to help her back up. She’d have had to figure it out on her own. (Side note: why are the coffee beans in the fridge?!) In the real world, family and friends would’ve labelled her toxic or not getting on with life and found excuses to no longer visit, call, email, text her, never mind valuing her ideas. I think that’s the least believable part. Brain injury makes you instantly not worth following your advice or adopting your knowledge/experience and crediting you. Sure, people will tell you that’s a good idea, but they won’t help you run with it nor will they adopt it to improve on what it is they’re doing. In the real world, the teacher wouldn’t have adopted Sarah’s idea; she’d have either ignored it after praising Sarah for her innovation or not brought it up.

I have to say there’s no emotional heft to the ending. It’s a nice bowtie but completely devoid of reality. I assume a few get to live surrounded by love and support, able to work at a job that accommodates their brain injury, valued by new friends and old, but I haven’t met any including myself.

Since this novel is set in the US, I found the lack of referencing the ADA a bit puzzling. Workplaces in Canada can get away with not accommodating because either provinces have no laws or the laws are not enforced, and the new Federal law is pathetic. The USA is far ahead of Canada in protecting the rights of people with disabilities.

I gave the book four stars on Goodreads mostly because after a decade I could actually read it like I used to before brain injury, albeit with visualizing and verbalizing not integrated fully like before. Also, it was easy to read. Sarah’s character was engaging, and I resonated with much of what she went through even though I don’t have left neglect.