I lost my Uncle Homi yesterday. “How do you mean you lost me?” I can hear him asking, as he quickly picks up on the many meanings of that statement. He was always an admirer of the more formal English of India rather than the more casual and sloppy English of Canada and the US and would not be too impressed with that first sentence of mine. So I shall amend.

Yesterday, after several months of believing that his end was near and a month after he suffered his first stroke and was admitted to a Québec hospital and then transferred to the more competent Ottawa General, my Uncle Homi, more precisely my father’s older cousin on his father’s side, died.

A big man, like his father and his father’s father, my Uncle Homi had told me back in early January that at his age he feared catching pneumonia the most. Of all the ways to die, that scared him because he had seen his patients suffer terribly from that infection. I am amazed at how many people treat pneumonia as if it was the common cold — trundling out and about, shedding bacteria or virii willy nilly, putting more stress on their labouring lungs — rather than the deadly respiratory infection that it can be. Well, unfortunately his fears were realised, but he was stronger than the invading pathogens, and he won that battle. I wonder though if he was like my Grandma, who back in 1981 wasn’t too thrilled to discover that she had survived her quadruple operation when she awoke and who then went on to die of unknown causes (and presumably to join my Grandpa in the afterlife). Uncle Homi… (“Why do you still call me Uncle Homi? I told you to call me Homi!” I hear him averring.) As I was saying, Uncle Homi didn’t die mysteriously like she did, but like Grandma (and in a way, like Judy Taylor at the very end of her life) he was ready to pass on and was none too pleased to discover he was still here on earth.

Actually, he didn’t believe he would “pass on.” Let’s just say he didn’t believe “in all that nonsense.” He was eight when he told his mother and father that he would not wear the sudreh and kusti. Apparently, they didn’t say anything because they just didn’t. He stopped wearing the Zoroastrian ritual garments — except when it was expedient for him to do so, as for instance, when the Muslims and Hindus were warring in India in the 1940s or ’50s and he didn’t want to be caught in the middle and so found it useful to put on the visible protection of Zoroastrian ritual garments — because he literally couldn’t understand the prayers. He didn’t speak Gujrati, and I assume his mother, who did, taught him the prayers in that language. He found it all a bunch of mumbo jumbo anyway.

He told me some time ago that he had made funeral arrangements with a local funeral home in Ottawa both for himself and his wife Addi. He didn’t want a lot of fuss or any of that nonsense, referring to the Zoroastrian prayers. Like most religions, Zoroastrianism has funeral rituals. They are designed to assist the soul in its journey to heaven, and I think, to help the living accept the fact of the death. Priests come to conduct the prayers for three days (Zoroastrian priests are volunteers), at the end of which time the body is buried. It’s important for the body to be buried as Zoroastrians believe in the resurrection of the body. That’s why traditionally, vultures pick the bones clean on the Tower of Silence in Bombay. God then uses the bones to knit together the body in the resurrection. Of course, that was a surefire reason why Uncle Homi told the funeral home that he and Addi were to be cremated. His soul didn’t need assisting — was there even a soul? Nope, none of this resurrection nonsense for him, no matter what his parents had taught him. Rebellious to the end, he further instructed no funeral, no memorial, not even an obit. He was to pass into oblivion unobserved. Sigh. Stronger creatures than I am could not have budged him on this decision of his, no matter how much they would have argued for the needs of the living.

But having that same rebellious streak, in smaller measure, I am writing this remembrance to Uncle Homi (“Homi! Not Uncle Homi!” Yet he smiles broadly as he remonstrates me, again), writing out my feelings of loss, writing my way to coping with an earthly life without him. I may not have been able to say good-bye in the traditional, time-honoured way that tells the heart “he is gone,” but I can say good-bye in this way, in a way that lets me know with finality that he is gone, for at the end of this post is a gallery of his photos. I would not be posting these — I would not even have possession of his photos — if Homi was still alive. If he was still alive, I’d still be looking forward to receiving one of his autographed photos for my birthday or Christmas. But I’m not.

Homi was a passionate amateur photographer. He was first and foremost a physician, and being easily bored, he switched specialties and homes a few times, finally settling down to the community life of a well-loved GP in Ottawa. (Apocryphal but true: He had to take an IQ test for medical school. As he couldn’t believe anyone wanted this as a measure of his competence, he doodled along in his boredom until test time was up. His mark was so low, it was, as he told me, at the “level of a moron.” That was technically an IQ of 51-70 at that time. The “moron” relied on his excellent memory to always come first in medical school.) But he also loved photography. I saw his cameras today: Comtrax and Zeiss Ikon. Three. With very different lenses. And very heavy too, for they were of a well-constructed vintage I haven’t seen since I was a child. These three were his current cameras; I didn’t see his other ones.

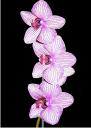

A few years ago, he closed up his dark room, metaphorically speaking, and moved it onto the computer. Now being Homi, he held no truck for these new-fangled computers. He liked the original Corel Ventura just fine, the version that Corel produced after buying Ventura and its utilities from Xerox. I liked it too, but being the computer geek that I was before Y2K, I really, really liked buying a new computer built to my specs every couple of years or so. That meant, of course, new software. Not always, but sometimes. All that newness and challenge of learning kept me happy for awhile. But the very idea of upgrading horrified Homi. Win98 suited him just fine. Dial-up was good enough. And the old Corel Photo-Paint gave him the control of fixing his photographs bit by bit, or occasionally pixel by pixel. I used to work on graphics with Corel Photo-Paint at the pixel level in my old pre-injury days, and I know what concentrated and skilled work that is. Retirement a couple of years ago meant he could devote more hours to that sort of work…when he wasn’t writing his newest book, that is. He was writing about water. I wonder now what will happen to all his research… But I shall not mull on that, instead I present to you my favourite flowers of Homi’s and a farewell nod to his three beloveds in life.